(Originally published March 2021)

Between 2014 and 2020 I had the rare opportunity of working for two cutting-edge hockey programs.

With the McGill Martlets (USports Women’s Hockey), I was introduced to the nuts and bolts of pressure-based, shoot-and-retrieve hockey by head coach Peter Smith, a two-time Olympic gold winner with Team Canada WHKY. In three years we won two provincial titles and two national silver medals while controlling close to 60% of shots at 5v5.

With the Toronto Maple Leafs, I learned from Kyle Dubas, Darryl Belfry and Sheldon Keefe about how scouts, player development coaches and bench coaches can work together to maximise a player’s potential while reimagining how a team can play the game.

At the intersection of the two experiences is the thesis of modern, attacking hockey:

On every play, good players (and teams) aim to improve the condition of the puck.

In the Defensive Zone

1) Get off the wall

Research conducted by Thibaud Chatel, Brendan Kumagai, Mik Nahabedian, and Tyrel Stokes, the winners of Big Data Cup 2021, illustrates the first and biggest impedement to possession hockey.

The goal of defensive-zone coverage is to force play to the outside, turn 0% possession into a 50/50 puck battle and then create 100% possession.

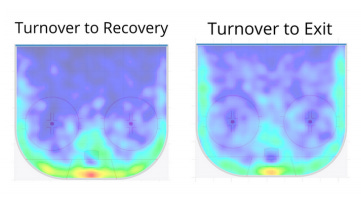

Most turnovers end up low in the zone, in the green, yellow and red areas in the heatmap above.

The best way for the defending team to transition out of the zone with possession is to force a low battle under the goal line, then get off the wall by finding a play into the ocean of blue in the middle.

TOR3 Justin Holl forces the play wide on a CBJ entry, steals the puck under the goal line, maintains his speed rather than get “stuck” on the wall, then finds a middle play for a teammate.

2) Beat F1

The habit of getting off the wall is a must for every skater on a proficient possession team, but elite players go one step farther.

Instead of merely making continuation plays on a DZ retrieval, they give their teams a mini-power play by beating F1 and finding high-value real estate in the middle.

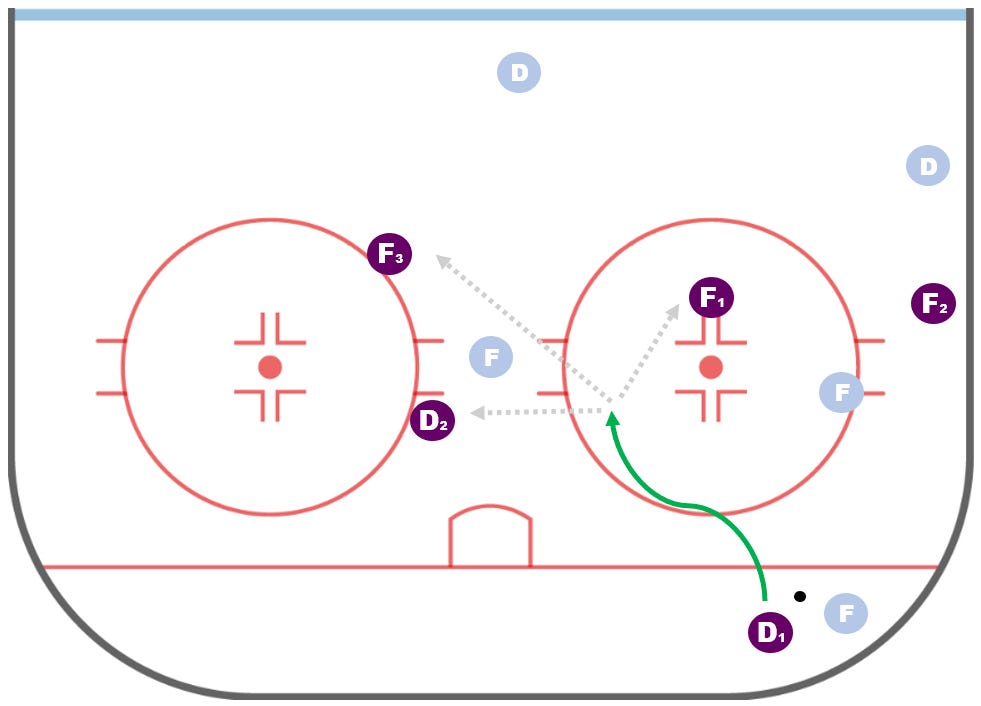

D1 makes a high-end play on the retrieval, using deception and skating ability to roll off the first forechecker.

By continuing with the puck and finding the middle of his zone, three high-quality plays between the dot lanes become available.

This small 3v1 ensures a controlled DZ exit, which is the best predictor of a future controlled OZ entry.

The uncontested middle carry is seldom available against an NHL-quality forecheck, but note how the Colorado Avalanche (above) use a mix of deceptive retrievals, quick carries and accurate passes to support in order to beat F1.

In the Neutral Zone

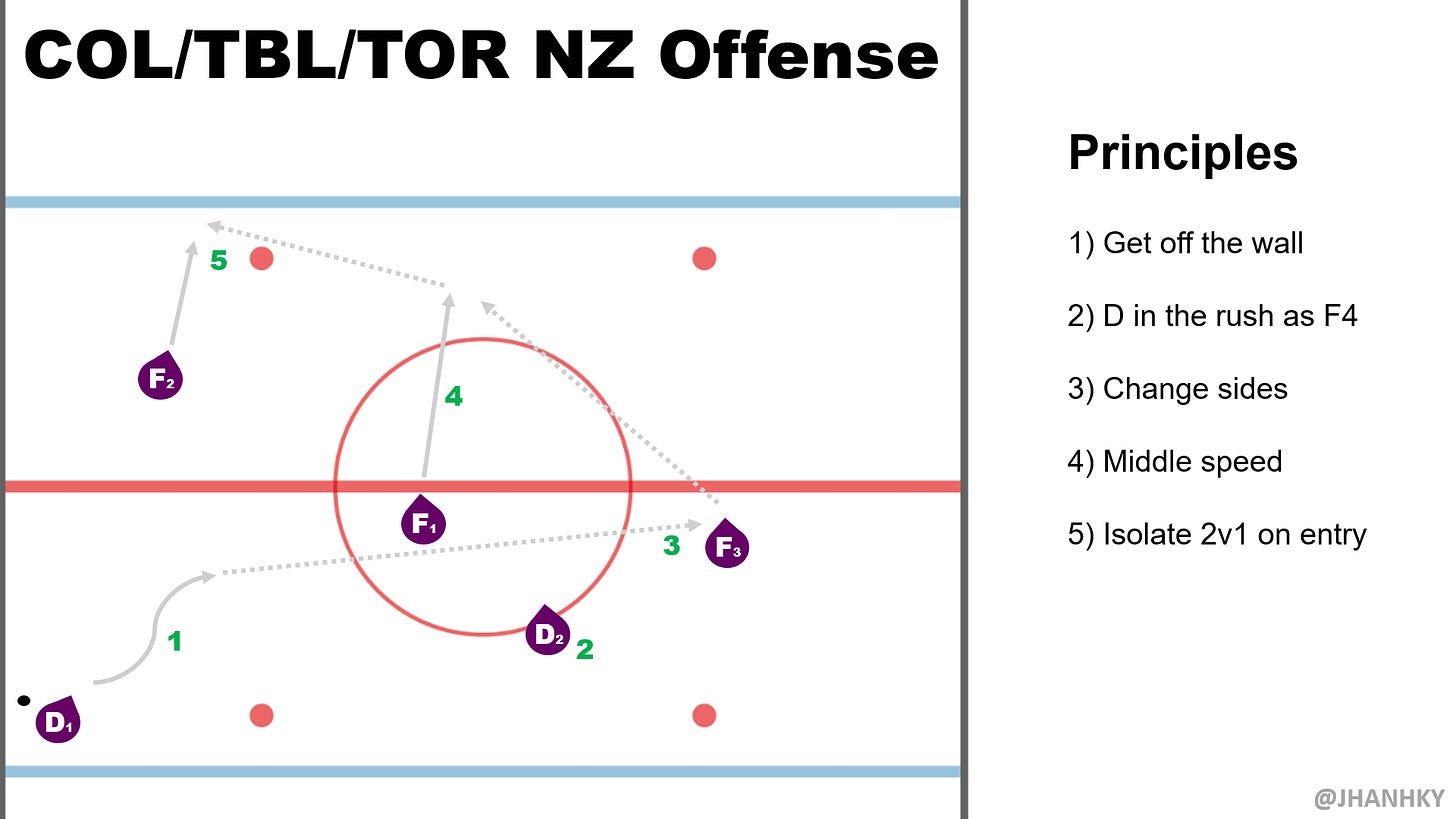

Against a well-executed 1-2-2 or 1-1-3 NZ forecheck, it is not sufficient to have the three forwards lead the rush and have the Ds sit back and cover the potential counter-attack.

To progress through the neutral zone with control of the puck, possession-oriented teams now to look to get a fourth player involved in order to create width and speed differential.

1) Create Width

As on breakouts, there is a clear emphasis on getting off the wall and into the middle. Thereafter it’s a matter of threatening all three lanes and using change-of-side passing to access the best option available.

NYI20 is the weak-side player and the hardest one to reach on a right-side exit. But a quick pass north + a bump to dot-lane support unlocks the high-value change of side pass, leading to a controlled entry + shot combination.

2) Create Speed Differential

After the change of side, there is the change of speed.

Having thoroughly researched the Soviet transition game for a recent ebook project (Hockey Tactics: Retrospective), I now understand why players trained in the USSR prefer to circle back and slow the play down when their opponents set up in a neutral-zone trap.

The 1975 Montreal Canadiens play an extremely passive 1-4 to clog the middle, but the Soviets use a clever inversion play to burn through coverage and score.

The idea is to create maximum speed differential between the eventual puck carrier and the opponent’s NZ structure.

The way to do that is to send both Ds up-ice, have them anchor near the far blue line and have the Fs curl back, build speed, and quickly exchange the puck to open a seam into the OZ.

This diagram might be familiar to you:

Indeed it is the exact same thing as a Double-Drop power play breakout, simply the most effective scheme at helping the offensive team gain the line and set up at 5v4.

In the Offensive Zone

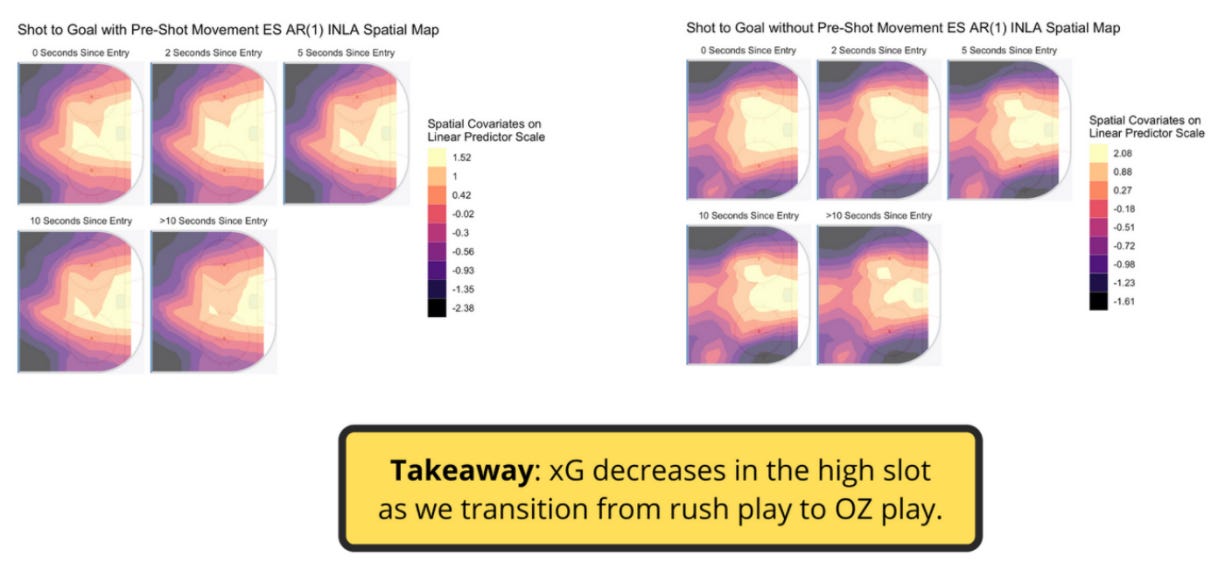

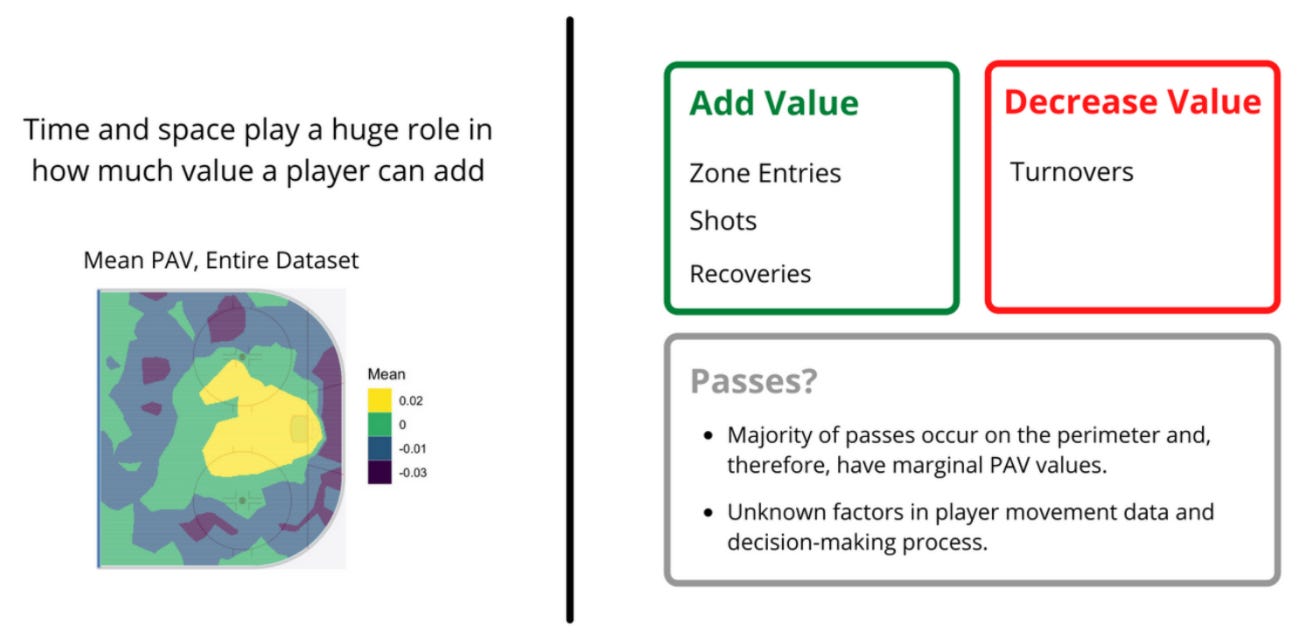

As Chatel, Kumagai, Nahabedian and Stokes conclude, there is a significant dilemma facing teams once they gain the OZ blue line.

The longer they wait before finding a play to the net, the less favorable their situation becomes.

The heatmaps below show that the high-value playmaking area shrinks quickly once a team enters the OZ due to defenders sorting out their assignments and collapsing to the slot.

On rush plays (0 seconds since entry), the high-value area in yellow is almost twice as big as it is on extended OZ cycles (10+ seconds since entry).

There are two tactics team can employ to conteract this phenomenon.

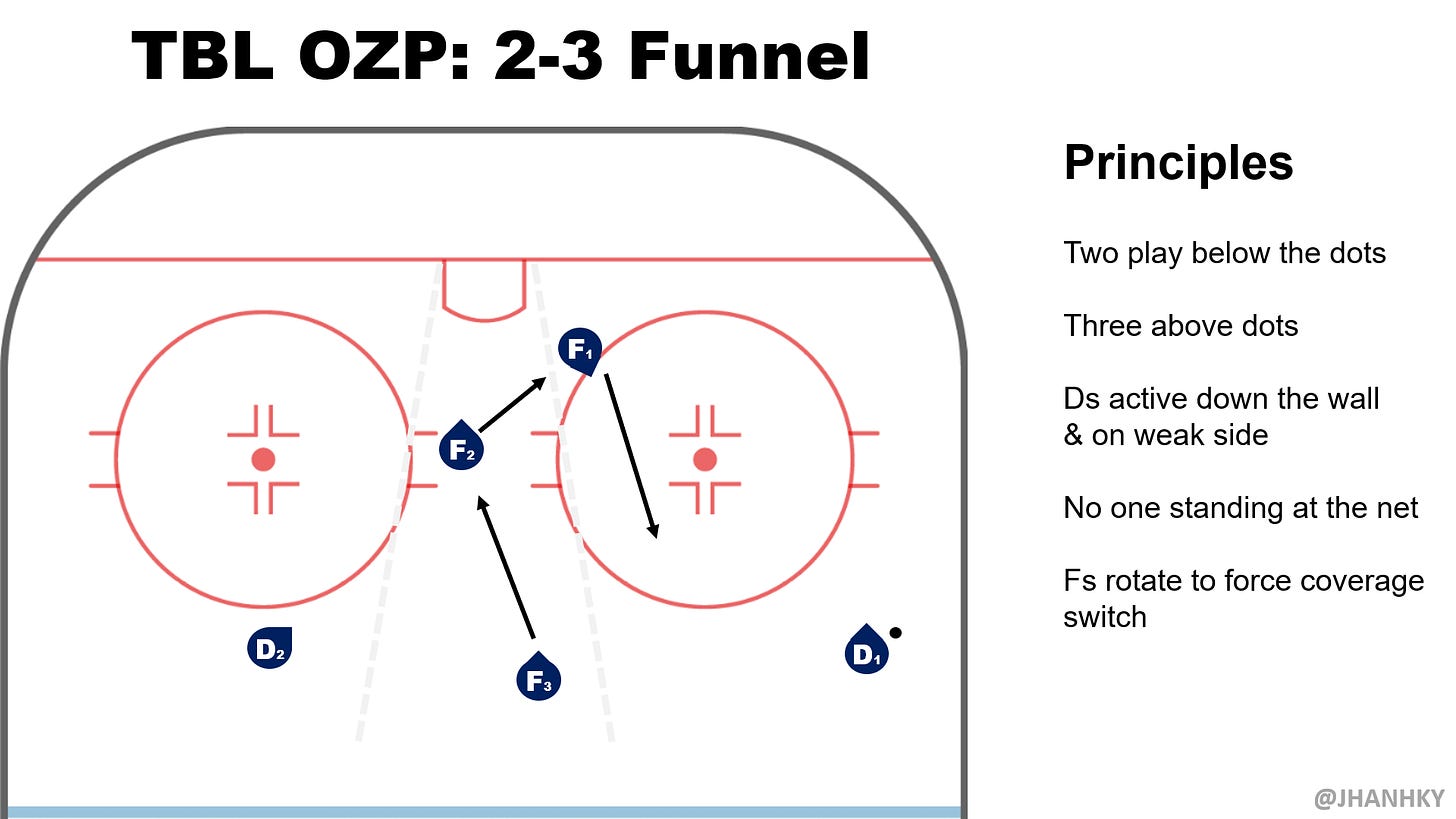

1) Move Through the Funnel

By placing three skaters high and by giving up the net, Tampa can cycle players in and out of the offensive funnel in the middle of the rink.

TBL’s opponents are faced with two painful alternatives:

Play man-on-man to match TBL’s movement (thereby causing an incredible amount of defensive confusion)

Ignore the movement and rely on switches to cover the unpredictable threat (thereby conceding a speed differential and a spacial disadvantage)

Off-puck movement through the Funnel is simple to implement across age, gender and skill levels. Here are the 2021 Connecticut Whale employing a similar pattern after a series of remote coaching sessions.

Notice how the CTW players on the weak side (left) move alternatively toward and away from the net. The first player backtracks and skates down the funnel while the second attacks the back post. MIN’s defense collapses to address the back post threat, opening up a lane for a shot from the high slot.

2) Shoot and Retrieve

The possession style relies on accurate passing and purposeful movement.

But ultimately hockey is still a shoot-and-retrieve game.

The 2017-18 Toronto Marlies dominate the AHL regular season, then win the Calder Cup playing mostly a pressure and shot volume-based style.

As the years go by, the team graduates its best players to the Leafs, but also begins to rely on Soviet-style regroups and Tampa-style long OZ sequences.

Results measured in shot, goal and win differentials begin to decline.

The intricate new style and a continued emphasis on scouting for control (as opposed to shoot & retrieve) players creates a feedback loop.

By 2019-20 the Marlies are a non-playoff team in a high-pressure league where many players cannot execute OZ cycle and NZ long regroup plays with the requisite success rate.

In the same season, the Tampa Bay Lightning get over the Stanley Cup hump by finding the right balance between carrying and dumping, cycling and shooting; possession and pressure.